How a critical decarbonisation supply chain has been disrupted and what it means for Australian consumers

Most of us will look for a climate friendly option when shopping for a new car over the next decade. The cars we will consider will feel different from our internal combustion engines with batteries and an electric motor.

Not only that, but the electric vehicle (EV) we will choose might also have a different, unrecognisable badge on the front.

This would represent a dramatic shift in traditional supply chains, coming from companies that would have existed for a fraction of the time of the established 100+ year old European and American manufacturers.

Chinese Dominance in EV Manufacturing

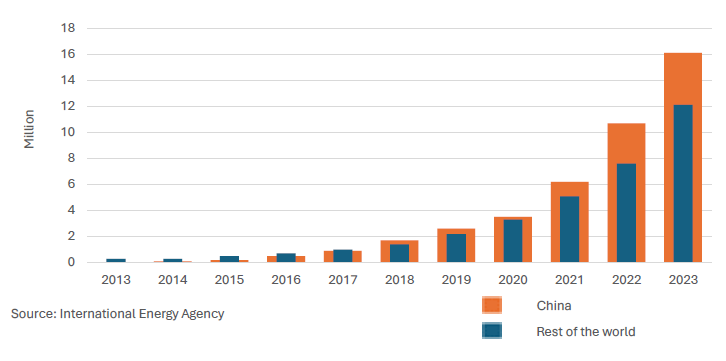

To say Chinese electric vehicle manufacturing has developed a lead undersells their sheer dominance. In the Global EV Outlook 2023, the International Energy Agency reported that 60% of global EV sales (~4.2 million) were in China and 35% of all exported EVs were from China.

Global battery electric car stock, 2013-2023

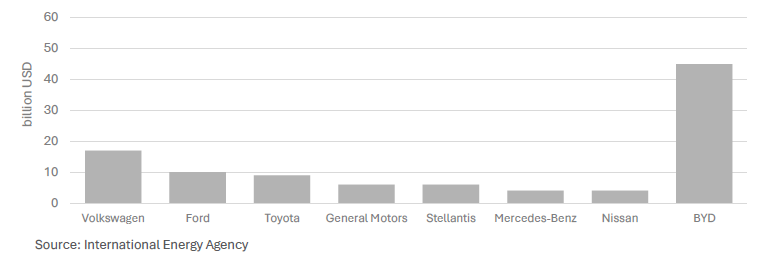

Electric Vehicle manufacturing is fundamentally different from developing an internal combustion engine car. This difference has resulted in the need for new manufacturing layouts, approaches and factories and has been a major use of funds for vehicle Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and recent entrants. Existing OEMs are reinventing while new Chinese manufacturers are starting with a blank page – electric vehicle native.

Annual CAPEX and R&D spending commitments on EVs and digital technologies by selected automakers, 2019-2022

Leveraging Competitive Advantage

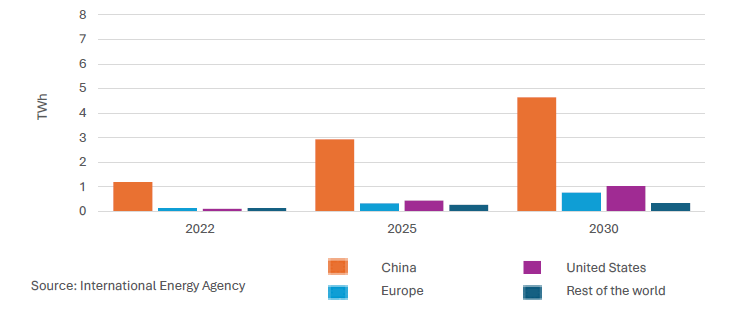

The vehicle’s battery has also been a challenge for traditional OEMs as it requires significant expertise and vast economies of scale. Subsequently, the battery is a primary driver in cost and range for electric vehicles. China has excelled in battery production and the downstream impact on electric vehicle manufacturing with no sign of Europe, the U.S. or the rest of us catching up.

China now faces the need to grow its export market with excess production capacity positioning markets in Europe, the U.S. and Australia as viable pathways.

Lithium-ion battery manufacturing capacity, 2022-2030e

Around the world, Chinese vehicles are being called out for build quality, software sophistication and range. We see this being a byproduct of the extreme competition within the Chinese local EV market and the latent software expertise needed for vehicle development.

Today, China is mooted to have over 300 EV brands. This number is dynamic with regular new entrants and exits reflecting the intensity of competition. For Chinese EV manufacturers, only but the best products or most efficient manufacturers would be expected to survive.

All of this has, in many respects, written the first act of the great electrification of the automobile.

This first act has ultimately re-written the status quo through its introduction of other brands. Previously, a global supply chain produced cars (that we bought in Australia) from countries such as South Africa, Thailand, Japan, Korea and the U.S.

Now, China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment in the EV supply chain is booming. Factories are being built in expectation of a requirement for more local content in markets around the globe. At the same time, domestic sales, boosted by healthy tax subsidies, are expected to grow a little slower at a still healthy 14.7%.

Build Your Dream or Build Your Own?

China’s progress presents a complex proposition to Australia’s federal government.

The existing vehicle market is dominated by traditional OEMs that make cars in Asia. Two top selling Australian vehicles have been utes (‘pick-ups’) made by Toyota and Ford in Thailand. The country also produces many other vehicles for the Australian market thanks to a free-trade agreement and supportive Thai government policies.

But with China’s global reach gathering pace and early industry dominance, Australia could continue to source its vehicles from Asia, but they would have very different brand names from the one’s we are accustomed.

For our supply chain decision makers, there are several benefits of this outcome.

People may be able to buy an EV sooner as prices are lower (even with the prospect of tariffs) leaving available capital for other electrification. This would be good news for our emission profile and response to climate change.

The cars themselves might also introduce new technologies such as Advanced Driver Assistance Systems and even SAE3, 4 or 5 capabilities that may arrive sooner than if we stayed with other traditional options.

But it’s not all smooth sailing.

Unfortunately, this influx could pose a digital sovereign technology risk for Australia. This has been navigated before and resulted in a ban (Huawei – 2012, then again in 2018). Other flow on effects to the broader electrification landscape (via batteries and software) may also challenge other global trade dynamics. For example, existing roles within the supply chain that are serviced by local aftermarket groups may find it difficult to support the new brands.

Negotiations for Australia’s own critical metals might also be impacted by our reliance on the new crop of EVs. Finally, the very real need for EVs may also lure other countries to incorporate Chinese manufacturing (Aion and BYD have factories in Thailand and plans for Indonesia), potentially isolating Australia in terms of availability of models

Some countries have already made up their mind.

In May 2024, the U.S. clarified their future manufacturing intentions, announcing a 100% tariff on Chinese made electric vehicles that will see the U.S. prices of those products rise. Chinese brands that manufacture in the US will be exempt from the tariff.

Green Means Go

EVs will be a cornerstone of our electric lives in the future and we need different brands, models and solid technology that brings new functionality and a thriving second hand and aftermarket industry. More and more consumers are expecting that an EV will be their next vehicle purchase.

Given the need to act, the development of a strategy that can chart our transport transition is critical. This would plot the interconnected nature of decisions that relate to:

- South East Asian manufacturing and Australia’s supply chain

- Critical metals and demand for our future resources

- Local technology and advanced manufacturing content

Ultimately, whether we are driving a NIO or a Ford, will be decided by our government’s approach to whether we will want to build, or at the least, support our traditional partners’ existing supply chains.

One thing is for sure, the implications will be more than just a different brand.